Turn it up to 11 redux

Last week we talked about not playing ALAPATT (As Loud As Possible All The Time) and how you can enhance your playing by adding dynamics. How using dynamics help tell the story you mean to tell through your playing. We noted that if you want to be a better harper, you needed to work on dynamics.

Dynamics come from control of your hands and fingers. This control determines how your fingers interact with the strings. Expression (an outcome of dynamics) does not mean to play limply or weakly or barely or badly. Rather, we want the same rich, warm tones you get at full volume, but at different levels of loudness. You can do this!

Remember, this is not about playing louder or softer. Rather, it’s about controlling your fingers on the strings, learning how to get what you seek from the strings based on how you move. It’s a delicate dance between you and the harp strings. In this case – you have to lead! To gain this control, I want to give you some exercises that will allow you to focus on learning to control your dynamics.

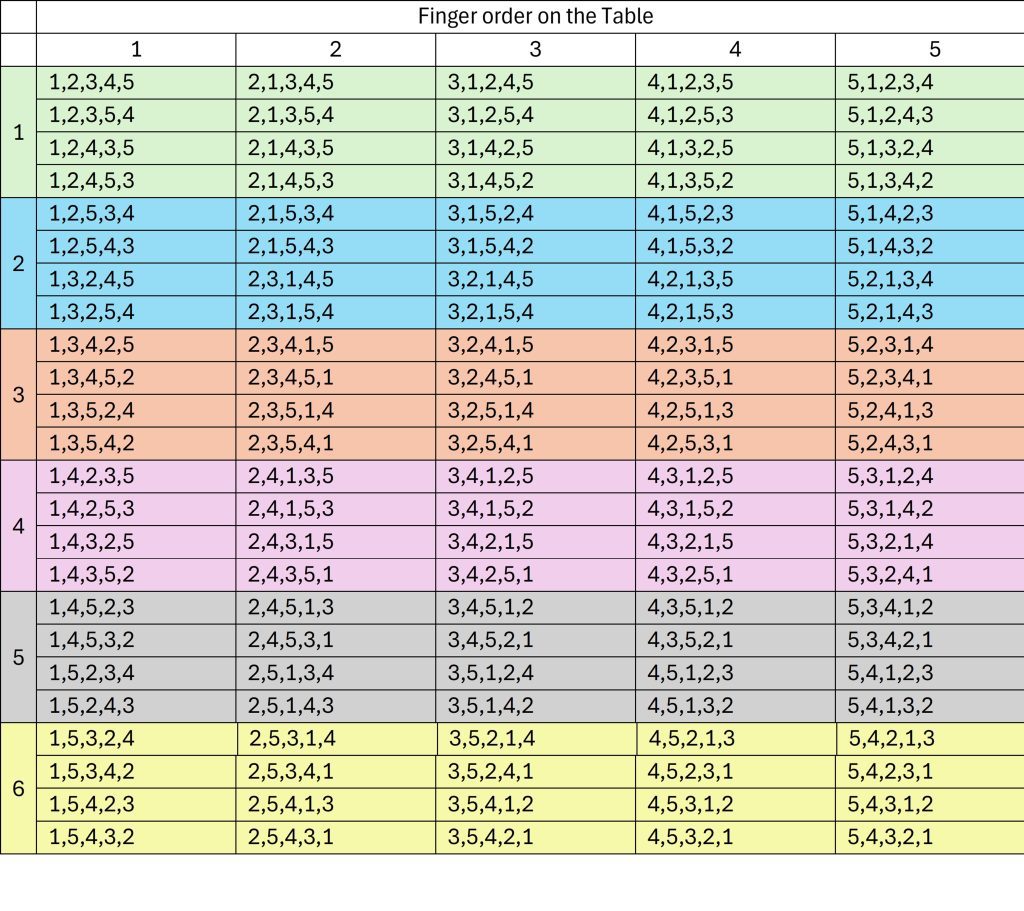

Let’s start by reviewing the dynamic markings. If you’re not familiar with them, they indicate the loudness for a particular section of music. These run from incredibly loud to incredibly soft (but still audible). The word for loud is forte (noted as f) while the word for quiet is piano (noted as p). There is also the range between them, and more letters indicate more (of that). So f is loud (forte), ff (fortissimo) is louder than that, and fff (fortississimo) is even louder still. Likewise, p (piano) is quiet, pp (pianissimo) is quieter and ppp (pianississimo) is even more quiet, but still heard. Smack in the middle are mf (mezzo forte) and mp (mezzo piano) which are moderately loud or moderately soft.

There are a few exercises you can incorporate into your practice to get better at playing throughout your dynamic range so you can master your fingers and tell the story you want to tell. These exercises are not difficult and a few minutes a day will train your fingers and your brain to work together to get what you want. The focus of the exercises is to build differentiation between ppp and fff with clear progress through pp, p, mp, mf, f, and ff and to be in control of your fingers for each.

In control means that you play what you meant to when you meant to.This requires good technique with placing and closing, so if those are still something that you have to think about, then get that ingrained and then work on this.

Also, this is a relative continuum (meaning there is no absolute “loud” or “soft” only really really loud, really loud, very loud, loud, quiet, quieter, really quiet, and “what?”).

The exercises can be piggybacked onto exercises you’re already doing and I’ll use a scale as the example. I chose the scale because 1. I’m sure you’re already doing scales every day already (right?); 2. Scales are important, safe, and accessible to all levels; 3. You already know them, so you don’t need to spend a lot of cognitive energy on remembering the notes to be played which allows you to focus instead on achieving the dynamics; 4. you’ll quickly know when you don’t get the result you wanted/expected.

Here goes:

Play one octave scale (up and down) in both hands at fff (as loudly as you can – while maintaining good form while staying in rhythm and tempo).

Now, play one octave scale (up and down) in both hands at ppp (as quietly as you can – while maintaining good form while staying in rhythm and tempo).

Third, play one octave scale (up and down) in both hands starting at fff, then repeat the scale each time starting at a progressively quieter dynamic (so fff, then ff, then f, mf, mp, p, pp, ppp. Each time through is a different dynamic). Yes, that is 8 times through the scales with graduated volume.

Next, play one octave scale (up and down) in both hands starting at fff, and subtly shift through fff to ff to f to mf. This takes a little planning – decide before you start to play where you make the shift – and how you will do that! Move it around a little and have some fun. For instance, you might do most of the scale fff and “downshift” to mp in the last 3 notes. Or play every two notes at a particular level. It’s up to you – the important thing is, did you get what that you expected? Don’t forget to do the other side and play your one octave scale (up and down) in both hands starting at ppp, and subtly shift through pp to p to mp.

Once those are easy(er), you can really shake it up. Rather than moving gradually from one dynamic to the next, adjacent dynamic, make big leaps! Maybe go ppp to ff to mp to fff, etc. You get the idea – big changes…just like you’re playing music!

Go slowly and carefully at first. Each time you learn something new you need to give yourself time to process it, think about what you’re doing, what’s working (and not working), make changes, experiment, and learn. Give yourself time for all that! Make your own variations – rather than playing both hands together play from one to the other (for example – fff from left hand up an octave to right hand for another octave and down at ppp or something else that challenges you a little bit but doesn’t stop you from learning).

When you are able to successfully do each of these, then do the same exercises but make the movement between loudnesses larger across multiple octaves. At first make really big adjustments from fff to ppp at the crossover or vice versa. Change up which direction you go (loud to quiet or quiet to loud). The point is to test your control (and decision making).

Just about the time you think you’re big and bad and hard to diaper, it’s time to do the really challenging exercise. Because real control will be having different dynamics in each hand – a quiet base line under a loud melody. Or a shift of the melody to the lower register (and in the left hand) with a quiet harmony in the right hand. Remember the idea is to control your hands and make good decisions.

Here we go – Play the bottom of the octave only (e.g., C-D-E-F (up to but not through the cross) in each hand. Select which hand will play fff and which will play ppp. Give it a go. Now, this is much like when you first tried contrary motion – you might feel like your fingers are connected to someone else’s brain! Just breathe and keep on. You want to have each hand doing its thing (now you see why you have to practice!). And when you are feeling pretty confident on this, then do the whole octave up and down.

If it doesn’t seem to be coming along, try letting one hand come ever so slightly before the other so that you’re in control of each finger. Breathe. Relax. Work them closer and closer together until they’re simultaneous. This is hard – don’t rush it. When you think you have it – make a video to assure that you’re not getting tense (and that you’re keeping the dynamic distinction between hands consistent).

Important things to keep in mind (especially when it isn’t going swimmingly):

- Progress not perfection.

- This is about control not volume.

- Whatever leaves you thinking you’ve had enough and can probably get by without is exactly what you most need to work on.

- It will be worth it – when you bring tears to a listener’s eyes…and they’re not from painful eardrums!

Remember that even fast tunes have a story (of some sort). If you want to tell the story of a frenetic rave + chase scene from a video game, then by all means, keep thrashing away. But if you’d like to tell a more subtle story (Battle of the Somme or Flowers of the Forest anyone?) use your dynamics and tell it!

I’d love to hear how you get on with this – let me know in the comments! If, after reading this, you are a little lost, let me know that too – and we’ll work on it. And if you have other approaches, let me know!