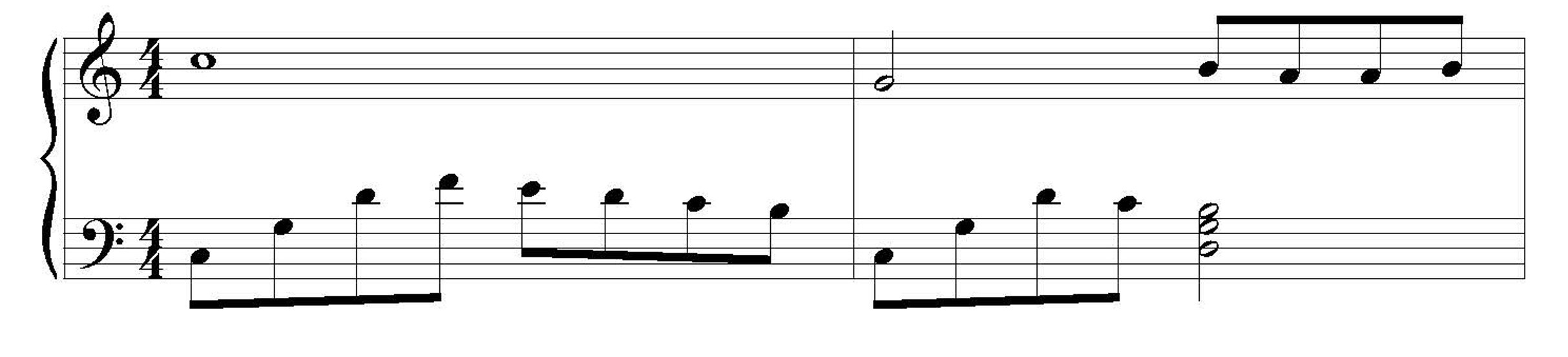

I often think about tunes in “layers”. All the layers are important, but some are easier to master than others. The layers include the notes, the fingering, the phrases. And then there’s the counting. There are loads of elements that define the music, but time might be the most challenging to really get learned and honed – to get right.

When you get to brass tacks, music is really a sequence of sounds and not-sounds (rests) over time. And so, to be true to the melody, share the message, and communicate with our listeners, we have to keep the count.

Sometimes, as harp players, we become inured to the silence – we get so little of it with our wonderful resonant instruments. Harps love to keep on playing and that lovely sound “hanging around” may make us lazy – it may feel like it will be easy to get away with not counting. But that is an illusion.

Counting can be a challenge when you first begin to learn a tune. There is so much to learn and all of it important. We have to keep the important stuff in mind – actively use it. Time is challenging but it can be so rewarding! It will help your audience follow your message, it will make playing with other musicians a greater joy, and it will help ensure your tune is what the original composer meant it to be.

Previously, I have said that I don’t advocate rigid adherence to the beat. That wasn’t really accurate. Rather, it is essential to know that timing of the piece and work within that. With poignant airs you might bend the time to build the expression, but that works best by manipulating the times. Laments need to be sorrowful, but it should never be lamentable! But the difference will be in how you deal with the time.

It is essential that you learn to count. Ok, I know you can already count. You have to learn to count while you’re playing…and keep counting, maintaining your counting throughout your playing. Only when you have mastered this tool of communication can you begin to modify its application as appropriate to tell your story. I know counting can be hard – it’s one more thing to do while you’re also trying to remember what notes come next, which fingers to use, that you need to breathe, etc. Pesky layers!

So how do you add counting to that task? Carefully.

First, start slowly. This really is another task you will have to perform while also doing all the other things you have learn. Counting is another thing you have to think about as you bring the tune together – make sure you go slowly enough that your brain can keep up!

Second, practice. Counting while you’re playing takes practice. You want to practice counting enough that it becomes automatic – no matter what you’re playing or where you are in learning it (just starting, polishing, anywhere in between!). One method I suggest is to include this in your practice away from the harp. An easy way to practice is while you’re walking or running. This gives you a physical beat to follow so you can work on counting.

Third, be consistent. You can’t practice counting the tune once and be done! Make practicing counting a regular part of your practice. If you really are not counting at all – start with simple tunes you already know. As it gets easier, move on to more challenging tunes and tunes you are learning. You will get better!

Finally, always be working on it. Once you can consistently and accurately count, start making things more complicated and related to other music. Remember to count to the smallest note value (e.g., the eighth notes if they’re present or 16ths – you will have to do some analysis). Use whatever counting device works for you – vocables, fruits and veg – whatever works!

Of course, there’s (always) more to the story, so send me your questions and share your insights in the comments. In the meantime, stand up for your music – make sure you count!