There are so many things we can do with our harps to make a noise – typically beautiful, but not always. And there are all the effects – from bowing the low strings to PDLT to damping to glissing – we have all kinds of ways to disturb the air and get sound.

We each spend time practicing our favorite sounds. Or those required by the score (Bernard Andres comes to mind quickly, but there are others…). We might even spend time actively seeking out new noises to make from our instruments or perfecting our technique to assure we get the effect we meant (harmonics come to mind). We work hard to get noises from our harps.

And of course, we spend a great deal of time learning to play so that we know exactly how to touch our instruments, so we get what we wanted – beautiful tone, deep, sonorous chords, compelling melodies, captivating harmonies.

But there is something else that we should practice that will enhance all this. We always let this get by us, and yet, it is often the secret sauce that really “makes” the tune. It allows the audience time to reflect. It gives you a space to think. It helps insert life into the tune. And it seems to terrify so many of us.

But there is something else that we should practice that will enhance all this. We always let this get by us, and yet, it is often the secret sauce that really “makes” the tune. It allows the audience time to reflect. It gives you a space to think. It helps insert life into the tune. And it seems to terrify so many of us.

What is it that we’re so afraid of?

Is it a technique that is difficult to master? Nope

Is there some “signature composer” that we should have already thought of (but we haven’t)? Nope

Is it some advanced riff that only the best musicians get? Nope again.

It’s the magical, useful, and all too undervalued rest.

You know – silence.

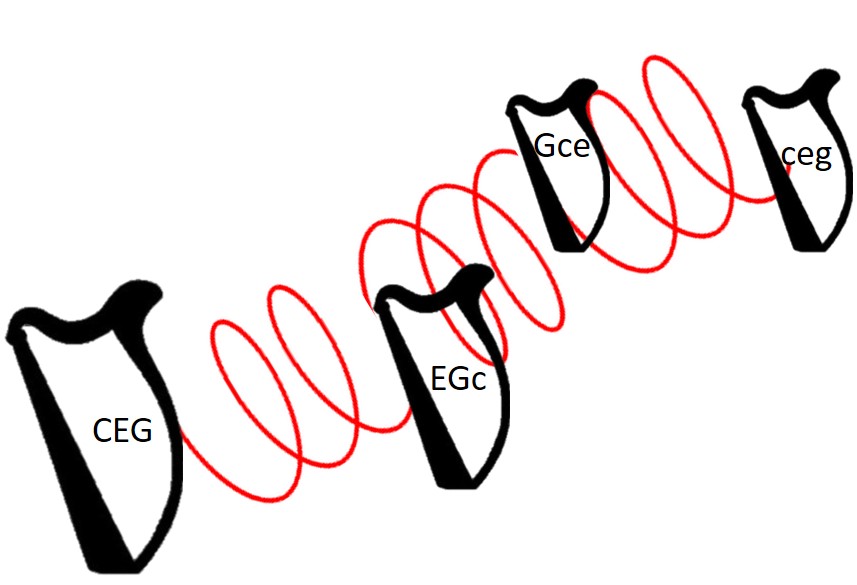

The space b-e-t-w-e-e-n the notes. The ones you might shave in the fast tunes (which is why you end up playing faster). The ones you wish you didn’t have so many to count in ensemble. The ones that can completely make (or break) your competition air. The ones that, when used appropriately, get your audience right where you want them, in the moment, with you.

Why do you need to practice your rests? Well, mostly so you will be comfortable – with the silence. We often “clothe” ourselves in the protective wrapping of notes. We think that we will be protected if we have the notes or that we are vulnerable and exposed in the space between.

How about you turn that thinking on its head. In fact, the rests are the most free part of the melody. Rests add a strength to the harmony that the sounded notes cannot. And they give you a little bit of a breather.

You already know how to make a rest. You just don’t play (or you also damp). And you don’t play for some finite amount of time (as described by the music). You create an absence of sound. You don’t generate any sound.

Of course, as you practice a piece, you would generate a rest if required by the composer in the piece. But, there are other useful times for silences – between pieces? Under thunderous applause? When you want to get the attention of the audience?

So, how really do you get comfortable with rests? Especially the long ones. Because, contrary to popular belief, that is not time made available by the composer so you can fidget! That’s true whether it’s a 16th rest or a thousand bars of rest in an ensemble piece. No matter how long or short, you need to wait, be quiet, and be ready, but not overeager, to come in.

Short rests are relatively easy to practice because they are a direct part of the melody. You can practice them with your metronome, just like every other element of the music.

For the longer rests, between tunes or to create a mood, here’s a suggested practice element. This can help you become more consonant with the emptiness of the rest. Use your watch (but only sparingly).

One of the most difficult things to do is to estimate how long you have been sitting, making silence. I had the opportunity to play for a meditative event. In this playing, it is important to leave a little space for thinking, praying, and contemplation. So, the rests become ever so much more important! A full minute is not too long to wait. I actually used my watch.

And learned something so important – when I had finished a tune and was waiting to begin the next, I had thought, “oh crikey, I better get going or they’re going to think I’ve fallen asleep.”

Watch check – 18 seconds. What?!? Only 18 seconds? It felt like a week.

I was aiming for 90 seconds. It felt like forever had gone by. Boy was I wrong!

After that, I start practicing estimating the amount of time that had passed since the end of the tune. (Reality check – to you the tune might end when you start to play the last chord, but to the audience, the tune ends when they can’t hear the lingering reverb any longer (or you complete your gesture) – which could be a while!)

My hack for estimating time – because it’s rude to check your watch over and over – is to sing the Birthday Song in my head. It takes about 10 seconds to sing (don’t rush it just because you’re not singing aloud). I breathe. I position (and then check) my fingers when I’m ready to play again. I don’t rush. Want to leave a minute? Sing the song six times through. To get 90 seconds sing it 9 times.

This ability to “tell time” without telling time will also make your presentation easier on your audience and on you. You can assure you leave some “breathing room” between your tunes. When you are not in a rush, you are more present which makes your music more lifelike and fuller. And what’s not to like about that?!?

So, incorporate full rests (no shaving of note value) and waiting rests (silences between) into your playing and Give it a rest! How do you make space for the silences?