I diverted last week because of the serendipity of meeting new ideas in the form of new people, but I’d like to get back to tuning because so many of you have asked for more help.

Month: October 2013

-

If I use my tuner I’m totally in tune, right?

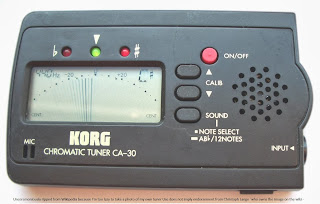

One question I have gotten recently is about using an electronic tuner. Full disclosure, I love and hate my electronic tuner! I love the relative ease it makes tuning, but I hate that it leaves my harp sounding not quite right. So today, things to love about your tuner and a couple of disjointed thoughts (that actually go together).1. Always check your calibration. Most of us intend to tune our harps to play with other people. The frequency we typically tune to is for the A above middle C to be 440 Hz (said, “Hertz” just like the car rental place). Be sure to check that your tuner is calibrated to 440Hz (this is a shot of my tuner – yours might look different if you have a different brand of tuner). See that in the upper left hand corner it says it is set to 440Hz? Check every time that it says 440Hz. On this particular brand it is quite easy to bump the calibration buttons (I once found that it had gotten to 447Hz – very sharp – it took me 34 of 36 strings to realize that my harp hadn’t suddenly all gone out of tune to the same extent! I had to retune the entire thing! That’s when I learned to check the calibration every time).2. You, off course, want to have that needle straight up and down with one green light. You want this for each and every string. Do not get frustrated, give up, and “live with” a string that it out of tune. In addition to that *not quite in tune* string sounding bad each time you play it with another string, you will be teaching yourself to hear that bad sound as “good” and soon you won’t hear it as bad anymore…but everyone else will.3. I know that you already know what I’m going to say next – tuning quickly and accurately comes with practice. The more you tune, the better you get at it.Now your harp is tuned. But it might not sound quite right…that is because it is in Tempered Tuning. Tempered tuning was designed to allow pianos to be played in just about any key. But to get that flexibility, the intervals between the notes had to be smushed a little bit. So, when your harp is “perfectly” tuned with your electronic tuner, it might sound just a little off (especially if you play a big, full, harpy chord with all the notes you can muster). Next week, we’ll talk about tuning by ear, why tempered tuning doesn’t sound quite right, and getting rid of that smushed sound. -

Hang out the “Open” sign?

The other day I was in my favorite over-commercialized caffeine dispenseria doing what loosely passes for work . Actually I was working, but I couldn’t help but overhear the people sitting next to me. I was trying to not listen, I really was. But their conversation kept catching my ear (no, I’m not about to tell you to listen more, although we can all do with the practice) – they were talking about breathing.

And every time they said the word “breath” I’d take one. And soon I was nearly hyperventilating! So, I did the only thing I could think of – I inserted myself into their conversation!

And met two lovely people, preparing a talk about breathing. We discussed all the wonderful things the simple act of taking a breath can accomplish – from giving one the time and resources to think, to helping clear one’s head, to making the music sing like it supposed to.I’ll beat breathing to death some other time, but for now, think about the serendipitous opportunities that arise every day. Are you open to learn when interesting people might share?

What has this got to do with playing the harp? Well, everything!

Be open – When you’re making music, you need to be open to experiences as they come along – whether you incorporate something new into your arrangement, play somewhere you never even thought of being, or play something you didn’t think you could, be open to what you may take away from the experience.

Be flexible – just because you’ve set out to do something in particular (play a piece a particular way for instance), be flexible if some other option arises (some people refer to this as a “jazz improvisation”), which will help you stay in the performance rather than focusing on the deviation.

Be interested – just as meeting new people are interesting, stay interested in your music, your technique, your performance – and your breathing!

Be there – if you’re not present when you are playing, how can you expect your audience to be there? Be present when you’re playing so you and your audience can enjoy the moment.

-

What scale do you tune to?

This whole series of posts has arisen because I am frequently asked to teach tuning. The requester is almost always sheepish about asking – they seem to feel that you shouldn’t have to ask. But really, if you haven’t been taught to tune, how will you ever learn?!? Typically get a very short instruction (pluck the string, twiddle about with the key, get the green light, go on to the next string) very early when you’re a little overwhelmed with everything!

You do need to know in which scale you intend to tune. You can tune to any scale but we tend to tune into one of a few major scales (please take this on faith, if you’re really interested, let me know and I’ll do a post on it later). Those scales we tend to tune in are C, Eb [read E-flat], or F (here too, I am going to assume you know the notes of the scales – if this is a wrong assumption, again, let me know and we’ll do that too!).C is familiar, it is a key many other instruments can play in, it “maps” directly to the white keys on the piano, and you are probably familiar with the scale from school music classes. You would use your tuner to get the following notes in the scale: C – D – E – F – G – A – B (and back to C) all the way up your harp. From the key of C you can get to other well used scales including G (one sharp – the F# [read F-sharp]), D (two sharps – F# and C#), A (three sharps – F#, C#, and G#), and E (four sharps – F#, C#, G#, and D#).

Tuning in the key of F gives you a very lovely and sing-able key. It does mean that you will have to raise one lever to get into the key of C but it also gives you a flat note – Bb. You would use your tuner to get the following notes in the scale: F – G – A – Bb – C – D – E (and back to F). From the key of F you can get to C (no flats or sharps – raise the B lever), and then move into the successive keys above (just start with the B lever going up to get you to C to start).

But you’ve probably heard lots of people say they are tuned to Eb. They may even look at you like you’re crazy if you say you’re tuned to C. DO NOT LET ANYONE INTIMIDATE YOU!! There is nothing morally or musically superior about being tuned in Eb. There, I’ve said it.

Many people tune to Eb because it gives you the most options to change scales without having to retune your harp. From Eb you can get to the most other keys – that’s the only reason to choose it. So if you tune to Eb, you will have to raise three levers to get into the key of C but it also gives you three flat notes – Eb, Ab, and Bb. You would use your tuner to get the following notes in the scale: Eb – F – G – Ab – Bb – C – D (and back to Eb). From the key of Eb you can get to C (raise the E, A, and B levers), and then move into the successive keys as above (just start from C to start). And you can get into the keys of F (which we have already talked about, just put up the E and A levers but leave the B lever down) and Bb (put only the A lever up). And of course, from this tuning with all the levers down, you are in Eb.

Now you can get around the scales a little easier and tuning might make more sense. As always – let me know if you have questions, otherwise I’m going to go on to other topics!

-

Everyone knows you have to tune.

Any sentence that starts with “everyone knows…” typically includes something that actually only a few people know and possibly even fewer understand. So, why do you have to tune?

Tuning serves many functions, some aesthetic, others functional. Let’s start with the aesthetic.

The harp makes a beautiful warm rich sound that we enjoy. Tuning is one of the many elements of achieving that tone. If your strings are not each in tune, the sound of each string will “fight” with the sounds of the other strings. This is not pleasant to hear. Even being off by a hair (as indicated by the needle and lights on your tuner) will be noticeable. And the more off your strings, the easier it is to detect that you’re not in tune. And of course, you will instantly sound better if you are in tune!

We habitually tune to an A of 440Hz. This is a convention – you can tune to any frequency you choose (e.g., Highland pipers tune A to about 470 – which is just about our Bb!). We elect to tune to A440 (just like a lot of other instruments) which allows us to come together as a group and play (or to play with other instruments). Be sure to check that your tuner is calibrated to A440 or you’ll be in for a nasty surprise!Now for the functional. Each harp is designed with specific tensions in mind. The harp maker goes through a great deal of work to develop the shape and sound of the harp and these calculations all account for the specific tension of each string as well as the overall forces of all the strings working together. Keeping your harp in tune will keep all the strings at their appropriate tensions and will allow the harp to work together as the harp maker designed it.And perhaps my favorite reason for regular tuning. Frequent tuning improves two things. First, the more you tune (read “practice tuning”) the better you will be at it (does this sound familiar?). Second, the more you tune, the better the strings will stay in pitch. Tuning the strings helps to “train” them so they require less tuning. Frequent tuning makes you more accurate and faster at tuning so you can get to playing!We will spend a couple of weeks talking about tuning because I have found that for something “everyone knows” many people are confused and a little afraid (or just plain tired of having to change out broken strings). -

Risky Business

No matter how many times you might step in front of an audience, it is always a little stressful. There is a lot on the line, whether you are playing to put someone to sleep or getting up on a concert hall stage – especially if it’s just you and your harp.

Why is it stressful? Because you are taking a risk! It might not, on the surface, be as dangerous as we typically think of risky behavior, but there you are, taking a risk. And we learn from very early not to take risks!One of the good things about leading a double life is that you have twice as much material to work with! I was talking with a colleague about risk taking – he was talking about Alpine skiing racing (literally – he started his skiing career in the Alps!). He’s even published work on this area: http://www.academie-air-espace.com/publi/newDetail.php?varID=180. But I started thinking immediately about performing.We can take a page from the book of risk takers – the tightrope walkers, skiing racers, mountaineers, and others. What do professional risk takers do to minimize the risks they take? Well there are many things, but here are three to start with – you can use them to improve your comfort when you step on stage:

1. Preparation – successful risk takers are prepared. They do not proceed unless they are prepared. They spend a great deal of time and attention to assuring that everything they need they have. You must also be prepared –know what “being prepared” means to you (determine what your comfort will require you to do), do not be bullied into performing before you are ready, perhaps schedule in “growing” time to perform for small, unthreatening groups (you might go from performing for your cat, to then performing for your sister, before venturing out to your church or other larger audience).

2. Routine – develop, practice and solidify a routine. The experienced risk taker understands that an established routine allows not only assurance that all is well beforehand but it also frees up time for your brain to do the heavy work you are going to ask of it while you are performing. You need a routine – pack up and set up your harp in a particular order, use a checklist if you need one, practice your set list, in that order, etc. Routine also allows you to reduce your worry (because it can improve your preparation) which allows you to focus on the music rather than on your fear.

3. Connectivity with people – Successful risk takers work collaboratively with other people. This connectivity provides not only support but also feedback. Build your connectivity with other harpers – you’re not in this alone. Find a teacher, mentor, friend who will provide you with honest, kind, usable feedback to improve your performance. Build what you learn from their feedback into your preparation and routine. And to build your connection – be willing to share what you know with other harp players.Go on – take a risk!